IN

PROGRESS,

PART II

At first, the fatal allusion did not seem to carry any effect beyond the ordinary. Pieter looked just like any other tow-haired Dutch boy, but then, at age six, he settled on his life career: photography. What? His parents could not fathom it, but despite them, photography obsessed him like a drug addiction from the earliest age when one fatal Christmas he received that harmless-looking, lego-toy kiddie camera from them. How they lived to regret that careless act!

It didn't help that there was a cultural bias. His parents thought their boy's penchant for photography a bit odd, since they were stock brokers, very prosperous ones too, in a long line of eminently respectable stock brokers. However, stocks and bonds and markets and futures bored Pieter to tears--he wanted nothing to do with stockbrokerage--which was tantamount to sin in their eyes.

Like a boozer and his bottle, that toylike camera could not be parted from him night nor day. He graduated to bigger and finer and more expensive specimens, of course, all the while honing his skills, which handily won him entrance and a top drawer scholarship at the best photography institutes of Paris and New York. After finishing with masters program (submitting one black and white photograph of his own choice), he quickly sallied forth as a free lance, taking assignments from various magazines.

One assignment particularly intrigued him and frightened his parents. After his friends weighed in against it, he felt impelled to take it, and stepped off the plane with his gear in Panama City, Panama, proud that he hadn't given in to people's silly fears for his safety.

Not wanting to interrupt his work, he thought that if he just went on working and ignored them, they'd fade away as unobtrusively as they appeared. How wrong he was about that! They just crowded in closer and closer until they were rubbing up next to him! Naked except for a loin cloth, each man was topped with strange headgear, and carried a spear in one hand and something else in the other hand he couldn't possibly identify--and, if this wasn't enough strangeness, they didn't speak, or if they did speak, it was by means of squeaks and rapid clicks of the tongue.

Strange as they appeared and acted, Pieter still wasn't afraid in the least these native people, just curious.

He noticed some other things about them. They had mutilated their noses to look like bats, he thought, but why go to that trouble? Were they bat-god worshippers?

He wanted to photograph them of course, to add to his pictures of the new hummingbird species for the magazine that had sent him to Panama, but his visitors rudely grabbed him. He found out immediately how extremely strong they were. He couldn't do a thing to resist them, they handled him like a doll with their massive, iron-hard muscles. They threw down his world-class camera and tripod despite his protests, and...kidnapped him!

Yes, he told himself, it was a genuine kidnapping, no question about it. He was somebody's captive. What was he to do now? He thought hard. He knew he had his rights--and they were breaking international law, and could be brought before a court, since he was a Dutch citizen. But what language did they speak? It seems an utterly nonsensical language he would never be able to alphabetize!

They gave him no time to talk his way out even if he could have mastered their gibberish-type language, or, failing that, to bribe them with something--money or a watch or a ring he wore.

Squeaking and clicking with calculator-like speed, they manhandled him head to foot as they hustled him through the jungle up and down steep slopes, and finally threw him into a small bamboo enclosure.

There they left him. For hours and hours, his hands tied behind him, he had time--but time for what? Everything of his former life had been taken from him by force. Now he had all the time in the world to study bamboo, ants of all kinds and sizes, poisonous centipedes, and how a man in his position sweated and felt other signs of discomfort.

As for ants, the whites ate holes in his clothes, while the red headed white ants burned him like fire when they bit him. The blacks attacked the white ants and left him alone. The tiniest ants were ferocious, and burrowed into his flesh with forceps-like mandibles that caused him great pain wherever they fastened on to him. He was constantly trying to shake them off him, or out of his shirt and pants, and he couldn't keep them out, as the white ants ate holes they could easily slip through.

But this, interesting to someone else maybe, was not at all what he had signed up for, not what he was trained to do, and he was becoming more and more upset and impatient and restless.

Over the hours, he worked frantically to free his hands, but they had tied him expertly with braided bamboo fibers, and he couldn't break them. Yet with enough work and the grease of his own sweat glands he managed to free one hand, and then he carefully moved aside one bamboo stake just enough so he could take a peek at his captors.

Whew! What ugly brutes they were when seen in repose! It was better when they were moving about. But now he could examine every horrible detail! Then he saw the bone litter around them. A horrible feeling swept over him. Were they actually going to COOK and INGEST him? Would their teeth masticulate him and his body tissues actually slide down their throats, swallowed, and enter their stomachs?

Why not? He had heard how there were many cannibals still in the wild regions of the tropics in tropical Australasia, so why not here in western Panama?

The possibility made him sweat, all the more he considered it. Why hadn't anyone warned him about these wild, unwashed, utterly uncivilized tribes of western Panama? It was hepatitus from impure water, and malarial mosquitoes, typhoid and parasites and jaguars, not to mention sharks and poisonous jellyfish and snakes that his friends warned him about--not the natives! After all, the natives were reputed to be pure, uncontaminated, noble souls--all living in perfect accord with nature and the eternal cycles of life and regeneration.

The filthy scoundrels! They had first taken all his gear away, then, worse, stripped him of his cell so he couldn't call out for help. He was at the mercy of these clicking, squeaking devils! Evidently, they had no regard for the authorities, human rights, and the Oslo Accords. If this was native culture, he wanted nothing more to do with any of it!

Why waste the carcass, Pieter wondered, then he remembered reading something about native cuisine, how certain rodents were rendered inedible due to poisonous oil glands. Evidently, this was the toxic type they were gourmandizing on. Too bad they knew the difference! he thought uncharitably.

One of the brutes then did something even more nasty. He relieved himself, right into the fire, and liberally sprayed the pot too, as the steam rose up and enfolded his companions!

Yet his unhygenic act didn't turn the edge of their appetites any, it seemed. His companions smacked their lips and wriggled their mutilated noses as the mighty hunter who shot the rodent stirred the mess in the pot with the rudely carved ladle--but only after he had wiped his nose with it!

Did these fiends know nothing about Dutch cleanliness? Their cook took the paddle spoon out from time to time, licking it with their thick, agile, dog-like tongues, then gave the others a lick or two in turn, before he stuck it back in the to stir again.

Acrid smoke of burning green wood sprayed with urine and a stench of stewing flesh and guts and burnt hair wafted over him--it couldn't be kept out of his bamboo enclosure, and he couldn't cover his nose with his hands.

St. Ursula! he groaned. Was he going to end up in that same pot with that awful rat and all those filthy guts? It was one thing being multicultural and diversity-minded in a clean, scentless, civilized setting, but here? Everything he had been taught since he was first able to go to school was now being challenged by these naked ruffians with the odd noses and outlandish headgear!

She had been going about her business, photographing the glyphs of the latest discovered Mayan ruins of Zatpotecacoatl when a gang of Indians (what tribe she couldn't guess at the moment), sprang out of the bushes upon her, and everything she had been doing was spoiled--as all her gear and film had been left behind, to get wet and ruined, no doubt, in the next tropical downpour!

It was all their fault! Whoever they were, she would see to it they were punished as soon as the authorities came and set her free!

She struggled to get free, nevertheless, from her bamboo bonds, just the same, as it was hard to tell when the police would come--though surely, they would come to inquire about her welfare--since she had taken the precaution to instruct her hotelier that should she not return by a certain date, he was to alert the authorities immediately and hand over a map she had made for them giving her exact coordinates.

A young woman, operating free lance (not by choice, as two porters and a cook had run off, taking a canoe with most of her provisions after only two days, crying some nonsense about "bat people"), had to be careful to make such arrangements, she knew. She had determined back at the university when receiving her degree, she wasn't going to end up just another "young, promising" researcher "missing in action," reported for a few days on the news, then forgotten.

But now, as the minutes stretched into hours, and the heat and bugs and her cramping arms and wrists took a toll on her patience and stamina, her assurance of rescue began to wane as well.

She realized that if anyone was to help her, it had to be herself, or nobody.

She listened to their strange, rapidfire clicking-squeaking speech of the Indians squatting round a fire only feet away from her, the constant smacking of their lips, the other rude sounds they made too regardless of a female's presence, and wondered how long she could endure their odious company without screaming?

Funny, she thought, she hadn't thought of screaming before. It wasn't encouraged in civilized society, true; even in self-defense, hardly was it mentioned. But why not do it? Maybe it would draw her rescuers, she thought. They were evidently having trouble finding her in the terrific rain forest undergrowth, after being hauled off from her work camp set in the tomb of a Mayan noble or prince an earthquake had fortuitously opened to view.

She estimated she couldn't be more than a couple miles off that map she had made, for they didn't take very long to stop and make camp, but the jungle was so thick and claustrophic, whole Mayan cities once containing tens of thousands of inhabitants had been swallowed up in it, and were invisible even to low flying aircraft. So how was she going to be spotted, if she couldn't be seen? No, she had to be heard first, and that meant using basic equipment, her vocal chords, which, fortunately, were still in great shape.

Wendy drew in her breath, and...

Only five or six feet away in another bamboo enclosure, Pieter's pity party came to an abrupt halt as he heard the most horrendous, earsplitting scream he could not have imagined ever coming from a human being--or was it human? Maybe it was a howler monkey? He could not tell at the moment.

The infernal, heart-stopping, blood-curdling scream finally ended, then it sounded again, only louder, shriller, if possible.

At the first scream, there was a a deathly hush in the Indian camp. After the second, he heard sounds of scrambling and scuffling around, as the Indians evidently panicked and ran this way and that to escape. Peering out between the bamboo stakes, he saw the camp was deserted entirely, the bubbling stew left to boil and burn up in the pot if his captors didn't come back soon.

But it wasn't the stew burning up that worried him. He realized, with a terrible feeling, that his ticket back to civilization had just been ripped up! These noxious, evil, nasty bat-people knew where they had found him, only they knew, and he had to find them, or he would wander in the jungles, and perish. Fancy that! His survival depended on the very ones who were most likely to make stew or shish kebab of him!

But there was nothing for it! He had to find them before they vanished forever beyond his reach!

He could use his hands, so he scrambled to free himself of his bamboo cell, but yet another scream emanating from the adjoining enclosure stopped him from leaving. He turned back, pulling aside the bamboos, and his eyes met an indignant female's.

Startled, he sprang back. Then he recovered his senses,and called out, "Hey, who are you? I thought I was the only captive here. What's your name!"

The response to that was a series of unladylike expletives that burned Pieter's ears. Then more civil words followed:

"Hey yourself! Now get me out of here!" the young woman yelled.

Pieter could tell this unknown female was serious. He was soon at her side, helping her get free of the handcuff, and she stood up, rubbing her wrists.

Now what? he wondered, as he watched her.

What was he going to do with the likes of ? He needed to do only one thing: to run and try to catch the bat-people! This young lady was definitely a complication. He had to get rid of her somehow, but how? He wasn't usually so impolite to the opposite sex, as to just run off and leave them in the howling jungle without a word first of rational explanation.

But how could he explain it best to her and not get more screams in response?

"Well, I'm Pieter van Pann," as she stood and glared at him. He went on. "But I really must go now, you see. You are free to go too-- so maybe this is the last we will see of you, but...er, the fellows who kidnapped me--and you too it seems--are the only ones who know the way out, or at least where they found me. From there I can make it out myself, I think. Here, it is hopeless! You understand that, of course?

That I really must go--"

"What are you saying? You'd leave me here like this? Alone? How could you ever find me again? But then you inferred you wouldn't even be trying, it was just yourself that mattered to you. I understand perfectly these Latins are all products of a macho society, but you--really, truly, you're an absolute beast in my opinion to even consider doing a thing like that! Leave me to rot in this stinking armpit of Panana? Just try it! You're not going anywhere, unless we go together!"

Pieter was overwhelmed. He hadn't really meant to give her that impression, that he cared only for his own safety. What an appalling inference! He wouldn't just let her "rot," as she said. If only she could see his point he had tried to make. He just wasn't accustomed to taking female companions on his expeditions-- being free lance and all.

Once again he tried to explain this, but got nowhere, and soon stuttered to a halt, as they started panting with frustration (Pieter) and anger and female outrage (Linda) at each other.

Civilized discourse had failed both of them. She grew even more angry as he attempted to talk in more diplomatic terms, and got out a wretched account of the way he preferred to work in the field--which was uncomplicated and solo, of course.

If once he detected anything and suspicioned a guard,

he had him tortured until he confessed, then he was put to death. The same was done to any accomplices he named, all done quietly without trials deep in the palace dungeons. His spies were everywhere too, watching places where he was not physically able to be present, and they reported to him any irregularity. He kept voluminous files, but they were not written down--oh no, he trusted no one with state secrets--no, they were all in his head. Besides, fear was

the best weapon he held in his hand, he found from long experience. Maybe it was theft, or

seduction, or even murder and assassination.

If anyone was up to something,

the very thought of Popilius and his gimlet eye finding him out could stop that one from trying it. Then again, a little sorcery never hurt anyone's power base, he had found early on in his job. Popilius purposely cultivated his reputation of an Egyptian seer,

of his being able to see through walls and hear every word spoken and discern a man's secret thoughts.

His Egyptian roots served him well. Both his superiors and inferiors reckoned him

a great sorcerer just because he came from Alexandrea, that prolific breeder of thousands such.

He let it be known, in fact, that a great serpent, a sacred cobra, had nursed him in

a temple, after his mother offered him to the god. From his adoptive serpent mother, he had

learnt the arts of wisdoms and sorcery, and the

art of select poisons as well. Actually, the truth was far different and not uncommon. He had been a slave to a childless, elderly Jewish banker, and done so well as a youth

in his master's business that

before he died, the old man wrote his will and adopted him as a son and heir and freed him with a considerable fortune to make his way on or establish a trade or business of his own. Seeing that Alexandrea was

too full of bankers, he looked abroad to Roma! Once his

adoptive father honorably interred in a sumptuous pink and gold-veined alabaster tomb, Popilius had taken ship immediately for Roma, the greatest city of opportunity in the world for enterprising freedmen like himself with some capital to invest.

Arrived in Roma, Popilius Serapius wasted no time. Getting into the good graces of aristocrats and senators through special services, bribes, and expert banking advice,

he was soon hired by Nero's palace chancellor. Cupronius Specius Erattus, a thoroughly lazy nobleman used to having servants do

everything for him, the fellow despised anything so menial as handling books and accounts,

servants and kitchens and estates, so his assistant Popilius was put immediately to work to supervise the imperial domains and palaces. Erattus held the official title while Popilius Serapius did the actual work in the shadows. He didn't mind the worthless Erattus received Nero's accolades for his fine work, so long as he held the real power. Without exciting envy by

being conspicuous, Popilius continued in power after Erattus choked on an overstuffed dormouse and

had to be replaced with another Lord Chancellor. Erratus's successor soon found that Popilius

Serapius was irreplaceable, and his successor too found the same thing to be true, so that

Popilius continued emperor to emperor. He gained so much knowledge of the workings of

the palace machinery and wielded so much power, finally no one could rival or supplant him, he

was just too efficient and, just as important, knew too much for anyone to dare unhorse him.

He moved about with difficulty, however, so he seldom walked anywhere on his own two feet. Even in the palaces, in his own private rooms, he never took a step,

as it wasn't necessary.

A litter with eight litter-bearers, each muscled like a gladiator, transported him from room to room, hall to hall, wherever he went to inspect and direct how things should go.

Another thing he supervised was the daily schedule of guests and visitors. Important as they might be, as a

shrewd master of protocol, he had a final say about them, whether they gained entrance and exactly how long he allowed them to be on the premises. A key man like himself, with that much power and girth, was someone to reckon with! Nobody got around Popilius! He had

been in charge since early on, from Nero's earliers days onwards, and he wasn't about to retire, though he was showing signs of age and slowing down a bit. His one vanity, his hair! What hair remained to him was reddened with henna from imperial farms in the province of Asia. A special ship brought it in to Ostia, then it was carried by his own porters directly to his quarters, as he risked nothing to insure his henna

was of the highest quality without a single chance of adulteration in the common markets. This way he also

insured no rival or enemy slipped in something poisonous too--always something to keep in mind in

a palace society of poison experts.

As his hairdresser, an expert Greek, applied the henna freshly to his newly washed white hair,

no one else was permitted to be present. Kohl was also applied to his

eyelashes and brows, and powdered rouge to his cheeks, to keep his color up,

though additional color was not necessary, his Egyptian skin had

retained its color well enough after long years under a northern sun.

Given a mirror, Popilius studied his hair and face carefully. He

demanded some more rouge, and a little more henna for his

hair, then decided it was enough, and dropped the mirror.

He clapped his hands, and chair attendants,

admitted by guards, rushed into the room and bowed low, waiting.

"Wine," he said.

A bottle was rushed in to him, covered with a fine white

linen.

Water too was offered, to mix it in a cup.

When the glass was handed him, Popilius studied it for a moment,

smiled, then ordered the servant to drink it himself.

The servant obeyed and drank. When the servant did not drop and writhe on the floor,

only then did Popilius order a glass for himself poured from the same bottle.

After that, the bottle was no good, as it couldn't be given to anyone else to finish, and it was taken away

to be smashed, as Popilius never drank from the same bottle twice,

and he permitted none of his servants to drink his wine either--

being a scourge of drunkenness among the palace staff.

A spy came and was admitted, showing himself

first to the guards, who then attended him

into the presence of Popilius.

Popilius waved his attendants and servants

away, then listened to the spy's

bit of information.

Popilius's kohl-darkened brows lifted.

He clapped his hands,

and the attendants approached.

"Take me to the emperor, at once!"Unquestionably, Popilius Serapis was the chief authority (behind the scenes) in the governance of the Imperial palaces.

Indispensable, no emperor could think to do without him, for he kept everything moving efficiently

as if on a thousand well-oiled little wheels and levers. He also controlled the maintenance of the grounds, stables, carriage houses, estates, factories, ranches, and

villas strung out all over Italia, Sicilia, Gaulia, Corsica and Sardinia--everything the currently reigning emperor possessed.

He also oversaw the staffing, which mean he was life or death to thousands, slaves or freedmen. Soldiers and guards too bore his watchful, beady eye--as he knew all about how they were most likely to harbor an assassin

against the emperor.

Growing up in the shadow of a smoking mountain was never a serious concern to him as a boy. Earth-shattering quakes were another matter. Yes, he had heard of a great shaking six years before he was born, that wrecked hundreds of buildings and houses, great and small, in his city, but most all that damage had been repaired and new and even larger buildings were built to replace what had been damaged. His teacher had read him the philosopher Seneca's own account of the quake, and Seneca was the teacher to the Emperor Nero! No wonder Roma had taken notice of it. Not only Pompeii, but his own home had been knocked mostly flat. His father, Cassius Ancus Semptimius, with a large business in garum, fish sauce for which the city was famous, was not ruined by the loss of the old Samnite structure. With his saved capital reserves he set out to make everything much bigger and better. He had supervised the complete rebuilding of the house from its foundations, while enlarging it considerably by taking over two older houses, leveling them, then building on their foundations.

Their house now promised to be one of Pompeii's most luxurious and biggest. But, of course, their residence was modest in comparison the Great House he had seen, one of the most luxurious, able to rival even the best houses in Roma.

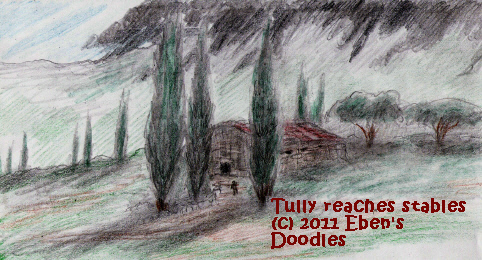

After his Greek pedagogue, Hymenaeus, was finished teaching him and went to his quarters several blocks away, Tully ran to the work in progress and had fun talking to common workmen and hearing their crude stories--he thought little about the cause of their being there.

One painter painted some hairy satyrs--lusting, goat-like men fondling naked nymphs--and his father saw it and had him paint over it with flowers and fruit baskets, olive wreathes and such innocent trifles. Tully had been in other houses and seen these wicked, hairy satyrs, so why couldn't his home have them too?

He didn't dare ask his father, so he asked his mother. "You're not old enough to look at such beasts and their naughty antics," she replied, though he was nine at the time and thought himself old enough. "You must wait a bit more, and then your father will tell you what that is about."

Well, he didn't wait! He ran first thing and asked the workmen. They told him everything! One even drew what he was talking about, which made Tully's eyes widen and his mouth hang open. He was astounded. That is what men did to both women and sometimes even other men? His father came back in just then, saw what was going on, called the house guards and had the workmen thrown out, with their tools thrown in the street with them.

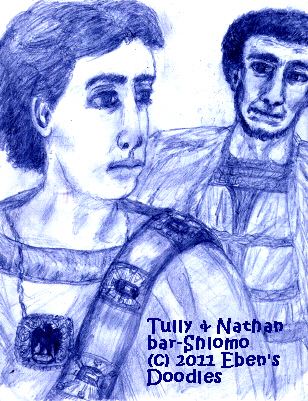

At that moment a friend of his father's, Nathan bar-Shlomo came calling, saw the disturbance, and Tully creeping behind the pillars heard his father explain what the men had done, inflaming his young son's tender ears with their lewd orgies with prostitutes.

His father's friend made a comment that Tully never forgot, though he didn't understand it. "They are but ignorant men, they are slaves to their base desires. After all, this city is just another Sodom or Gomorrah."

"Yes, it certainly is, thanks to the Romans!" his father agreed. "Ever since the Romans came, this city has never been the same! But not here, not in my house! We Samnites still believe in virtue and noble, clean living. That is what made us strong and resolute men, able to endure life's troubles and hardships."

"You are a good man among your people, and a good father, Cassius Septimius," the friend declared. "You will always have my business, even if my God is not yet yours, and you still throw incense to your vain Greek and Roman idols, and even the Emperor Vespasianus as a god, though he is a mere mortal of flesh and blood like us!"

"Be careful, dear friend!" his father cautioned. "You are free to speak your mind and religion in my own house, but the Emperor may have a spy nearby listening to us, and throw us both in the arena with lions and leopards like they are doing the followers of Christus in Roma and other places up in Gaulia, I hear! And if you should ever persuade me to give up my gods for your one nvisible Jewish God, why I would lose all my business in a day--since you Jews are too few in this city to keep my business prosperous!"

Whatever was said after that, Tully did not stick around to hear, for they were coming his way, and he had to run quick, or be caught eaves-dropping. He was frightened now. After the affair with the naughty painters, to be caught listening from behind the pillars to grown-ups, he feared his father would severely discipline him. He ran to his mother's room and pretended nothing had happened. After a while, he went to his own room. He climbed up into his window and sat gazing out at the chief sight, Vesuvius Mons.

There they had a close view of the gladiators as they fought and trained, and sometimes seriously wounded each other. For that reason, his father would never take him there, thinking him too young to see bloodshed and other things that went on there among the rough, hard-drinking, carousing and womanizing men in the school.

His father was talking to his friend, and only later did Tully see him when they had dinner, which was set up on the terrace in a garden, the triclinium for dining outdoors. The subject of what happened to the workmen did not come up, fortunately for Tully. He hardly knew what he was eating, wondering all the time what his father might say. Strangely, his father never breathed a word about it, nor the part he had played.

Instead, his parents discussed something else. "I'm sorry your dear friend is not here to dine in our new triclinium," his mother said. "Didn't you invite him, Cassius? It would be impolite for him to turn down our invitation."

His father shrugged. "But you forget something important, dear, which they, being Jews of strict religion never forget."

"What is that?"

"They cannot eat our foods prepared as we normally prepare them. Meats and dairy foods must be handled and cooked separately. They use entirely different sets of utensils, that they use to prepare and cook with. Even the garum sauce we use and sell, they cannot use. So we make a special garum in the port factory without using unscaled fish. For the Jewish customers we have, only scaled fish will do in the sauce. I thought you knew that. We would have to prepare and cook their way, separating meats and dairy foods, using separate sets of utensils, pots, and dishes. They cannot even be washed and rinsed in the same scullery tub, nor can the same towel be used to dry both sets."

"Yes, I think I heard some of this before from you," his mother replied wearily, "but I never understood it, so I forgot it. I also recall you said they never eat pork. How can you have a tasty dinner dish without some pork?"

"Well, the Jews are very strict about their dietary laws, which they believe their single, invisible God, whom they decline to name out of reverence, commanded them to follow, but they are good people for all that, and I don't believe they mean any effront to us. My friend and good customer, Moshe bar-Shlomo, who always pays on time, isn't at all anti-Roman or a hater of our ancient Samnite customs, as some people say who would give them all a bad name--the Jews, I mean.

I could trust him in my home at any hour, day or night. I can't say that about most people we know! Even our families and blood relatives--I wouldn't allow them free run here!"

Then they changed the subject to something about the layout of a new garden and its decorations.

What a relief that was! Yet he never forgot that "Sodom and Gomorrah". Were they cities? The names were strange and foreign. They didn't sound like good places to be. What had happened to them? It was a mystery to him, and he didn't dare ask his parents. He had kept quiet and escaped a whipping, hadn't he? As his teacher said in Greek, "Don't ever tempt the gods, boy. If you do, they will crush you like my shoe heel crushes a bug!"

That was good enough advice for him! And another thing his pedagogue said: "Best leave sleeping dogs lie."

So too with the quake that destroyed their house six years before he was born. His parents did not speak of it, so he never really thought about the cause or connected it to the big mountain a few miles to the east of the city. His pedagogue, taking him outside the walls to teach him names of wild plants, herbs, trees, and even rocks that Aristotelius had written about, noticed something and pointed it out to him--the city was perched on what had once been a swarming mass of melted rock.

"But where did it come from, Teacher?" he asked.

His teacher pointed to the north, toward the mountain, Vesuvius Mons!

Tully couldn't believe it. "How could it melt rock and spit it out like the Sarno all the way here? What would melt the rock, Teacher?"

"If I take you to the goldsmith or any other smithy, he can show you that fire, when it is blown hot enough by the bellows, can melt rock, until you can pour it like water!"

Tully was dumbfounded. He looked again at the mountain. "But I see no fire on it. No rock is being melted there."

"Oh, but just wait! It may awaken and start a fire and melt rock again. Other mountains, one far south of here, Etna Mons is smoking and burning all the time. It is presently melting rock. Sometimes these mountains fall asleep, sleep for a time, then wake up and suddenly spew fire, smoke, and melted rock."

"Not our Vesuvius Mons!" Tully replied to himself. "It's always been sleeping like a lazy, old dog since I was born. It's not going to wake up for a long, long time yet! But I wish it would, I'd love to watch it melt rock and do those other things you say they can do!"

"Silly boy!" the teacher said, shaking his head as he left Tully. "It would bring the death of all of us and this city too!"

Tully soon forgot about his teacher's ominous words. Life wasn't that serious! Pompeii had everything a boy could want--and much more! It was always changing, being built in all the time since the last earth shaking. It was again a wonderful city. Theaters, gymnasium, gladiator school, huge swimming pools, arena, forums, markets of all kinds, grand temples, which were thronged with people from the cities all around and even from far parts of the world. He had learned several languages already, among the many he heard spoken by visitors.

With all this to interest and entertain him and his friends, why should he worry about the clouded mountain towering in the near distance? It had always looked that way since the day he first saw it--and hadn't changed, nor had it ever hurt anyone he knew.

He had climbed the lower slopes with friends too, and there was nothing dangerous about it, other than maybe some snakes and wild dogs. Much was covered with trees and plants, it was nice up on it. The bare, sharp-edged rocks and black, cinder-strewn slopes above the trees were harder going, of course, and the wind whipped at you, and it could get cold. Cliffs too--but they didn't venture to climb them, though some older boys claimed they already had done it and even bragged about how they had made it to the very top--though he didn't believe them. Someday, he vowed, when he was a year or two older, he would really do it! He just turned eleven, so he knew he would grow a lot soon and be a big, strong boy, able to reach the very top, where the eagles soared.

Tully was tremendously excited. It was like a holiday, only better than the ones for honoring various gods and the emperor, since his father was introducing him to his business affairs, just as if he were a grown-up! This was just as good as watching the gladiators train. which was strictly forbidden by law of course--but boys can always find peep holes to watch things that would shock even adults.

He already knew the businesses of the tradesmen that rented rooms where their house fronted busy intersections of streets--the shop that sold hot foods, and the tavern, and the taberna, and how they didn't want their landlord's son hanging around.

First, his father took him to a number of his garum customers, right into their splendid houses that were normally closed to anyone but select friends, family, and household servants.

"Whose baby was it?" Cassius S. asked his son. Tully had no idea. "Well, the king devised a sure test to reveal the true mother." "How, pater?" "He simply ordered a guard standing there to divide the child with his sword and give half to each. Immediately, as the wise king foresaw, the true mother was revealed, when she fell down in tears before the king and pleaded strenously for the child to be given to the other claimant, despite the fact she had approved the division of the child, since the king wasn't going to award her the whole child.

"No true mother would hesitate to give her child up to save him," Cassius instructed his son, to drive the point home. "I suppose so," said Tully. "But what happened to the other woman, the one who lied?" "What would you think happened? She stole her friend's baby, then lied before a king to keep him. She committed two crimes at the least, even showing contempt to her king the judge by seeking to deceive him. Of course, he ordered her to be severely punished."

Aaron's father entered the atrium with Aaron at that moment, catching Cassius's last words. "Ah, I see you are showing our great wise king and the testing of the two mothers to your son! He should profit by it."

"I am not sure he is yet old enough," Cassius replied doubtfully eyeing his son. "But I know I have profited. Your king proved himself the wisest man on earth. If only we had emperors as wise as this Solomon of yours! I find them nothing but fools and shameless beasts!"

Natan bar-Shlomo cleared his throat. "May I caution you in turn, friend Cassius, for that is daring talk even for you, a nobleman among the Samnites. If I, a mere Jew, were to say the same thing, and it was reported, I might find myself in deep trouble even though I spoke it in my own house!"

Cassius nodded. "By Jove, I will not mention the misbegotten emperors of Roma again for your sake. And please forgive me. I just misspoke, naming my god within your own walls."

Aaron's father inclined his head, accepting the apology.

All this was boring, political talk for young boys. "Could Aaron go with them?" Tully asked his father the moment the talk lapsed. Aaron was his best friend, he added.

His father consulted Aaron's father first. His wife came to greet them at this time, and so she entered into the matter. Since this was a special outing, and they felt they could trust their son with their friend Cassius Septimius, they approved it.

"He will learn something important about business," Aaron's father remarked, smiling. They escorted Cassius Septimius and the two boys to the delivery wagon, and the driver took them to the next customer, the House of the Vetii

It wasn't large like other houses of wealthy people, but the two merchants, Aulus Vettius Restitutus and Aulus Vettius Conviva, had spent huge sums to decorate it with wall paintings, statues, fountains and pools.

It was like a wonderland, a picture-gallery of all the best heroes of Graecia and Roma and their exploits.

But, strangely, Tully's father wouldn't let them look at certain paintings in the entrance hall which featured Priapus, the god of fertility himself, but everything else in the public rooms were allowed them to view while Aulus Restitutus conversed with Cassius Septimius.

"I can't look, it's an abomination, it's Sodom and Gomorrah in there!" Aaron blurted out. "I'll be defiled!"

Cassius S. then saw the wall-paintings, then glanced back at his son and little friend who was so upset.

"Son, you know better than to look at such things! They're not for children. I shall deal with you later."

He turned to Aulus R. "My son has misbehaved, so we are leaving now. I regret this happened. I thought they were old enough to accompany me--"

Aulus R. laughed. "I forgot to tell you this room was repainted last week, that's all it is. Don't hold it against the boys, Septimius! Lighten up! Boys will be boys. They won't see anything else that will offend your propriety. I beg your pardon for the naughty little bacchantes of this room if they offended you, but I got so tired of the floral wreaths and little birds, I told the painters to do as they wished with it, just so it was amusing to look at, and not so dull."

"Yes, I see they did as they wished!" Cassius Septimius observed wryly. "Just the same, I think it is time we were going. Good earnings, Aulus Restitutus!"

Back at the wagon, Cassius S. turned to Aaron. "Run along home now," he said. "Can you find your way, Aaron?"

"Yes, sir! I can!"

Aaron scampered off, leaving his glum-faced friend to his fate.

"You come with me," the father said to the son.

"You've shamed me before my patron and also the son of my friend the Jew!"

Cassius S. led him into a small open-doored warehouse, and found a notched measuring stick for the sacks of wheat and other grains.

They emerged a little later from the warehouse, Tully's face red and streaked with tears.

"Now will you behave, or must I send you home?"

"I'll behave, Pater! Please let me go with you! Don't send me home!"

Cassius observed the tears, and shook his head. "Your tears will not move me as they do your mother, but I will give you another chance. Just don't treat it lightly!"

They continued to the Forum, and the wagon, now empty of long-necked garum sauce jars, was sent home with the drayer.

In the heart of Pompeii the main Forum was bordered by the city's chief temples, halls of civil government and municipal offices, and halls of the major industries and trades. They had just started from the huge open court and turned into the Basilica, Ero passing overhead at that moment, when they were hailed by Nathan Bar-Sholomo, Aaron's father!

What would Aaron's father say? Aaron must have told him everything, Tully thought, and now...

He would have liked to run, but he couldn't--his father held his hand fast.

With his head down, filled with dread, he waited for Aaron's father to tell his own father what Aaron had said. Wouldn't Aaron make it worse than it was? And wouldn't he get whipped again when they got home? But Aaron's father started talking business.

Tully waited, hardly able to breathe, but still not one word about him.

Finally, his father gave his hand to Aaron's father to shake on their joining in a new business venture.

"I will be happy to join you and finance half the cost. You talked to the right official. How did you get close to him enough to receive your offer. Imagine that, we'll be supplying the garum sauce to the officers of four legions! The gods of fortune have smiled on us and our houses this day!"

"No, not the gods, my friend, there is only one true God. He is the one who smiled on us, and gave me entrance in the Capitol to the high official I needed to see, who had the power to give that contract, and then decided I was the man for it. My Roman name, Cavus Marcus Porticus, works well in Roma!"

"Yes, I know, you call your god of the Jews, strangely enough, the 'God of Abraham'--He is the one who favors you and blesses you and gives you such a sharp ear and eye for business."

"It is the truth, you know it is the truth, Cassius. You should have been there, seen Pompilius's vestibule and atrium packed with the most important men of business, all seeking what I alone walked away with! Our holy scriptures say, 'God promised Abraham our forefather, I will make you into a great nation...I will bless those who bless you, and whoever curses you I will curse; and all the peoples of the earth will be blessed through you.'"

Tully heard his father heave a deep sigh.

"Speak no more, friend, I am almost persuaded to become a believer in one God and worship your God! What sane man would not choose such blessing as you have on you over curses? But should we speak so openly of your God here? We might be overheard by an enemy of your people. I am Samnite, born of the most ancient aristocracy, and my people were civilized and city-bred, flourishing here for centuries before Sulla's legions put down our last resistance to Roma. Freedom was a nice thing, but we have been under Roma for a long time now and have grown accustomed to the Roman yoke on our necks and shoulders. You Jews refused to submit wisely as my Samnite forefathers did, so Roma destroyed your country, your temple, and enslaved your people by the hundreds of thousands--all those they didn't slaughter. Surely, Roma has a curse on her now for that, if your God is still the God you say he is."

"God never changes, if that is what you are asking! Oh, deep in your heart, you are a God-fearer, Cassius! Know that the One True God has his eye on you!"

Tully's father was edgy, and looked around. "But will he protect me as he protected your own people and country? Look how your own people the Jews were destroyed, and your temple burnt, leveled to the ground, and teams of oxen pulled plows over the cleared earth where your great holy city once stood. Why didn't your God deliver you from our legions, and the fury of Vespasianus and his son Titus? They were worse and more merciless than even Cornelius Sulla was to our city. He could have destroyed us, but refrained, reducing us to a colony but allowing some vestiges of local government here of our own. Is that what the blessing of the God of Abraham brings his people--total, merciless destruction?"

"No, my friend, that was punishment for transgressing his holy laws; but still his covenant with us holds fast, he will never forsake us utterly, he will bring us back to our own country, he will plant us there and make us flourish once again, as in the days of our greatest kings, David and Solomon his son."

"Ah, your great namesake, the wisest king on earth whose proverbs you gave me in a book, which I keep by my bedside. Thanks to him, I will not grow slack at discipline and spoil my son, like I see other fathers doing with their sons in this beautiful, rotten city of ours."

After a few more words, Nathan bar-Sholmo asked for a favor. "Certainly, what is it I can do for you!"

"My wife and I think so highly of you, Cassius. Here is the key to my house. We must leave and go to my father who lives in Stabia. Report has come he is fallen very ill and may not live long. I am leaving only our household servants. If we are gone more than a few days, would you go and look in, to see if things are in order? It would be a great relief to our minds if we could see to my father and not worry about our home."

"Of course, I am happy and most honored to render this service to you, good friend!" Cassius replied, taking the large brass key handed over to him and attaching it to his belt. "When will you be leaving for your father's home?"

"As soon as I found you and finished talking of our business! But now I am free to take my wife and son and go. I am anxious to be at father's side as soon as possible. As his eldest son, he depends upon me to handle his final affairs."

"I am so sorry to hear of his illness, and would pay for prayers for him at the temples of Jupiter and the others, but wouldn't offend you, so I will just commend him to your God's care, and not detain you a moment longer."

Exchanging the customary Pompeiian "Good earnings!" to each other, they parted, Aaron's father hurrying off to Tully's great relief, without one word about Tully's misbehavior in his son's company to disgrace him.

They proceeded toward the far end of the Basilica, toward the equestrian statue of Caesar Augustus that stood in front of the Tribunal where all the civil cases were handled.

"Son, I have to check on my petition to the emperor, son. Remember how I told you we lost most of our lands and vineyards, and businesses--the laundries, bakeries, laundries, dyeworks and cloth weaving, when Sulla took them? All we were left was our garum manufacture and the little shops round our house. Remember the great house I took you to, to see the big floor picture of Alexander the Great fighting Darius, king of Persia?"

"Yes, Pater! I liked it very much! May I see it again?"

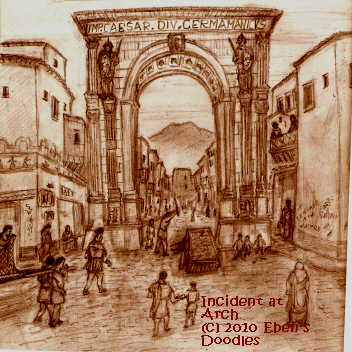

"Well, perhaps. Anyway, that great house was built on our property with our lost fortune. Sulla is little thought of these days. We may get back some things back if the emperor approves my petition. Our family has tried for generations to get compensation, but we could never reach the emperor's attention, whoever the emperor was each time our family applied with a new petition and the necessary bribes. But our city has risen in imperial favor since then. Vespasianus has his temple here, and a villa on the mountain slope. The Governors erected an arch to Germanicus and numerous statues of the members of the imperial families adorn the public places. Noble Romans have their villas here, sparing no luxury on their embellishment. All this was bound to help us in my suit, son. We cannot be ignored as in former days when we Samnites were still considered conquered, inferior people by Romans. Samnites have come to occupy some of the highest positions. Who knows? Today we could even hear the disposition of the case."

Tully wasn't sure he understood all this adult talk, but he caught parts of it.

And Cassius Septimius was right, he was not to disappointed this auspicious day--this 24th of the month of Augustus. They had just climbed the finely made wooden stairs to go to the entrance doors when four men came out of the Tribunal. Cassius recognized two of the men as the city's duumvirs, the dual-serving Governors of Pompeii. The tallest of them, Governor Publius Lucanus Torenus spoke for his peer as well as the others, greeting Cassius with a beaming smile.

"Pater, you're hurting me!" Tully gasped, trying to twist his hand free.

Cassius realized he was gripping his son's hand like an iron vise, he was so overwhelmed by what the City Governor was declaring to him.

He let Tully go, so he could rub away the pain. "Pardon me, son, I can hardly believe this much good news--"

He turned back to the smiling Torenus.

"Excuse me, Governor, I am somewhat shaken by such good fortune falling so suddenly on me, I nearly crushed my son's poor fingers."

"Yes, I can understand why you might find this news gripping," quipped Torenus. "But now our other suits can go forward on the tail of your successful one. We may even be awarded self-government, and with freedom rise to become one of the greatest emporiums and port cities of the empire, as wealthy and great as Antioch or Alexandria or Athens and Ephesus. There will be no limit to our expansion and trade and industry. What was hard for us before this time in our inferior status imposed by the infamous Cornelius Sulla, will be made easy in the days to come. Your success is the golden key that opens the door to a glorious destiny for our city! What a day this is to celebrate, both in your home, Most Noble Cassius Septimius, and throughout the city. We Governors declare a holiday to be celebrated four days hence, so that preparations can be made beginning now. You, Cassius Septimius, will ride with us in state chariots through the Arch of Germanicus and receive the people's acclamation. In the Forum, at the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, you will lay a wreath of gilded laurel--"

After the officials were finished giving Cassius instructions and congratulations, the governor again urged him to do the honors at the amphitheatre's new opening, after a ban of the gladiatorials for ten years by Nero and the Senate due to a very bloody riot between the Pompeiians and the rival Nucerians that left many dead and wounded, including some important officials and their Roman guards.

Cassius respectfully declined. He had some urgent matters at home to attend to, he informed them.

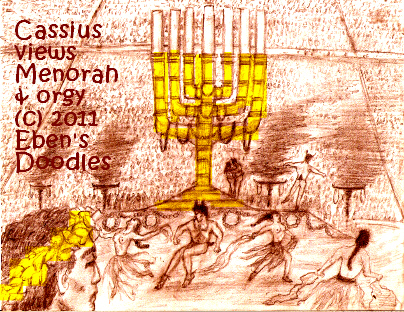

"Oh, but you must come, Most Noble Cassius! You cannot miss seeing the Jewish candlestick we brought down from Roma. The Imperial Treasury and Archives released it to us just for this occasion. Other cities have asked, but they were all refused. What with the dancers and music, it will be a sensation, the like of which we may never see again!"

Bowing deeply, he declined a second time.

Keen disappointment showed in the officials' faces, but how could he help it? Cassius thought, his whole being sickened at the thought of what they were describing. Gladiatorial "Games" were distasteful to him, with the crowds screaming to see more and more blood shed for their entertainment. He could force himself to go, but to see the actual sacred candlestick of the Jewish temple defiled? No, it was out of the question--even if he lost his suit and favor with the emperor.

He would never forget his last visit to the amphitheatre nine years previously, how the city had staged an elaborate tribute to Vespasianus and Titus and their crushing of the rebel Jews of Judaea. A huge model of Jerusalem was constructed, the Temple of the Jewish god most prominent, then gladiators in Roman army uniforms fought Jewish rebels, other gladiators costumed in Jewish robes and beards. A lot of blood was shed in this mock battle, but that wasn't the worst of it. When the battle was over, and the "Jews" crushed and the city and temple set aflame, surviving Jews were strung up on long rows of crosses erected to form a giant Star of David. He and other prominent citizens all wearing laurel crowns of victory were then to form a mock-up of a triumphal procession and shout praises to Vespasianus and Titus for their great victories, waving banners while the tens of thousands in the stands celebrated. But that wasn't the whole story as it developed. Gladiators posing as Jews on the crosses were stripped naked of course. He had expected that. But when he saw he saw Pompeii's highest officials and chief citizens all joining in making the most vile, lewd fun with the naked, uncircumcised "Jews" on the crosses, it was so degrading a spectacle, he drew back. The crowded amphitheatre was roaring with laughter and could not get enough of watching their leaders make beasts of themselves. Yet the outrages of this paled in comparison with the centerpiece: a copy of the holiest object of the Jewish temple, the giant golden sacred candleladrum the Jews called the Menorah, was brought in by dancing naked women and satyr-lovers, and set on a stage. As the music of water organs and lutes played, the satyrs and the women danced around it, then copulated round the base of it. Satyrs copulated with satyrs too, to the vast delight of the crowds.

He recalled how he had run out of the amphitheatre, discarding his gilded laurel crown just beyond the gladiators' entrance where prostitutes plied their trade, inside and out of a nearby latrine.

How then could he explain his true reason--his utter disgust--for declining their invitation?

After expressing their disappointment and failing to induce him to go with them, the officials threw up their hands, shook their heads, and departed.

Cassius S. led Tully away with great relief, since he had stood his ground and not returned to the scene of such monumental horror.

Just the same, he felt somewhat weak and drained immediately afterwards, and a little afraid of the repercussions his refusal might entail to is business and social standing. He knew he couldn't deny the wishes of the governors and the high Roman official with impunity. No doubt they regarded his behavior as an effront to their dignity.

The temple of Vespasianus was nearest them. It was every Roman citizen's and subject's duty to honor the emperor's divinity and image, and Cassius Septimius was a good citizen of Roma, and hadn't the gods just now favored him in an extraordinary fashion as to restore his patrimony? Only had he not now risked the gods' displeasure, spurned their favor, by refusing to take part in the defilement of the Jewish temple's sacred candleladrum?

He paused, in the courtyard, and did not proceed to the altar where the priests waited on the temple's patrons to make donations and throw a pinch of incense as they recited their ritual prayers.

"Is the emperor really a god?" Tully asked candidly as a child would.

"The Senate declared him a god, son. It is our duty to honor him a god, and impious not to believe it."

"Yes, Pater," said Tully. "But Aaron doesn't believe he is a god, he told me so!"

"Don't you say another word! Just for that, we're leaving, and maybe the Genius of the divine emperor Vespasianus will send you a bad dream tonight or a bad stroke of fortune tomorrow!"

Yet his father wasn't really angry with him, for he took him next to the homes of some of Pompeii's wealthiest people. Servants let them in, knowing Cassius Septimius, even thoughWIDTH=500

most families were gone to the amphitheatre by this time.

In the finest house, Tully saw again his favorite, a magnificent mosaic of Alexander the Great on a horse chasing King Darius of the Persians in his chariot as their armies battled.

But worse, they came to an incident at the Arch of Germanicus, the mad, cruel "Little Boots," or Caligula.

"But he won't pull the cart, officer!" the drayer protested. "He just wants to lie down and roll his eyes stupidly like that! I don't know what's got into him. Yesterday he was just fine!"

The disgusted officer flung the bloody stick away the drayer had used.

"Get your cart and your filthy beast out of here at once!" he ordered. "Kill him if you please, but not here! You're blocking the road and disturbing the peace!"

"I'll kill him all right, and cut him into little pieces if he doesn't get to his feet soon!" the drayer muttered as he went to the nearest taberna to hire some fellows to help him.

Tully pulled his father's sleeve.

"What's wrong with him, Pater?"

"I don't know, son--his eyes, he seems paralyzed with fear of something, though you would think he would be more afraid of his master's club!"

"It'll make good dog meat if nothing else!" observed one man, the proprieter of the nearby, very popular gambling house for rich, idle youth, whose sign featured two phalluses alongside a tall vase.

While this scene was playing out at the Arch honoring the bloody Caligula, eager, excited crowds already taking the best seats they could at the Amphitheatre for viewing the restarted gladitorials and--already the rumor was being noised abroad--the grand exhibiting of the Jewish Temple's menorah complete with bacchantes and nymphs.

"Go and see to Sulla," Cassius Septimius told his son, while he hurried off to see his wife, whom he knew must have grown concerned about the strange disturbances.

Tully found Sulla was seemingly turned mad, scratching his footpads bloody as he fought to get free.

Afraid to even touch the dog, he stayed clear back as the dog lunged against his metal collar, which cut into his neck and choked him. Whimpering and whining, the dog's eyes rolled back in their sockets. He had even bitten his own tongue, and bloody sputum drooled from Sulla's mouth.

"Pater! Pater!" he cried.

"What is it?" his father said, gripping his shoulders to calm him.

Tully couldn't know what to say. There's blood, blood all over him!" he blurted out.

His father's face went pale but very stern.

"Oh, do something, Septimius!" Tully's mother moaned. "I cannot take any more of this! The gods are punishing us, for daring to put them aside for that awful solitary god of the bar-Shlomo Jew! And I don't believe a word of it, that we are getting all that money from the Imperial Treasury. It's all foolishness. It'll never happen! Romans don't care about us Samnites getting justice!"

Cassius Septimius flung her a glance to silence her, then took his hands off his son, whose shoulders he was gripping too hard and hurting.

He turned to the door, with cold, ancient, aristocratic Samnite dignity in his bearing.

"You stay here with your mother, son, I'll deal with Sulla, and the horses too. It won't take long."

He went out, and Tully forgot his weeping mother and stayed by the door, waiting and listening anxiously.

Then he heard it, a sudden, shrieking, horrible yelp, like a dying animal in mortal agony would make.

His father did not return, so he crept out and retraced his steps.

What he found was Sulla lying in a heap, twitching, but his eyes closed. Then he saw the wound in his chest, pouring out blood, and a bloody sword, his father's, lying close by.

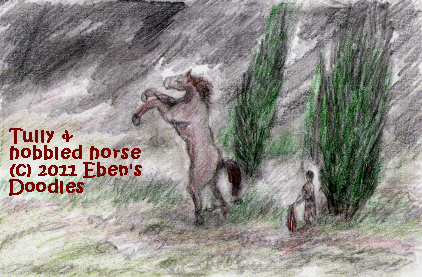

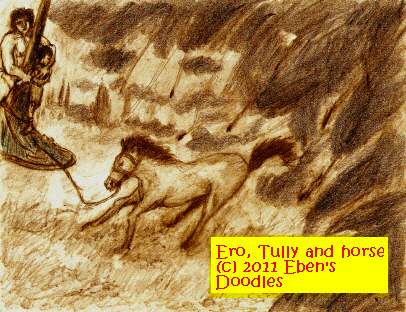

He hardly cared to do it, but he crept breathlessly to the stables. Peering round a corner he watched his father and the four stableboys lead out the snorting, stamping horses, one by one out the posticum and into the street.

"Take them to the fields and hobble them there!" his father ordered the men. "But make sure they have water. One of you stay. Calinus, stay and watch them, the rest of you return immediately. You, Cinnamon, on return, fetch the dog, for he is dead, and carry him in a grain sack and bury him someplace outside the wall. Take a shovel along too. You're broad of shoulder, you can manage it yourself. I'll look for another watchdog tomorrow. Clean up the dog's mess and wash all the stains. Do a good job! My wife is not to see anything if she goes back there--"

Tully didn't dare listen to more, he ran to his own room and hid in his bedclothes of his couch, his heart thumping. What had happened to cause all this turmoil? In less than an hour the whole household was turned upside down, and the city too seemed rocked all out of joint and its normal course of life!

The next day dawned like any other, the bright sun pouring in on the peristyles and the gardens and through the roof opening to the atrium. He could see the sun coming in his window, and knew it was time to get up.

He rose and washed his face in a basin a servant placed just inside the door, and used the towel to dry, and then he went to see if the cook had something. His parents rose later in the morning, usually. He was passing by their chamber when he heard voices, so he knew they were up--which was strange. He paused to listen, and heard his father speaking, with his mother interrupting him now and then. It sounded so serious to him, not like their usual conversations.

What were they planning? he thought, growing concerned. Were they going to move from Pompeii? The thought was horrible. Leave his wonderful city, which he liked so much? He knew there was none better in Italia. Even the thought of Roma did not appeal to him! Pompeii was perfect for a boy like him! He knew it, and loved his city. The thought of having to leave it for some villa elsewhere horrified him. Leave his friends and pastimes all behind? Surely, they wouldn't do this to him!

He was moving away when his father burst out the door, turning toward Tully's room. But he saw Tully and took his arm,

"You're just in time, son. Come in! Your mother and I have something for you to do."

Tully's heart sank. His feet dragging, he let his father lead him into the bedchamber. There he saw his mother lying on a couch in the shade of the room, her eyes dark with tears. Her hair wasn't arranged like it usually was--no servant had been called to do it in the fine coils she piled up on her head.

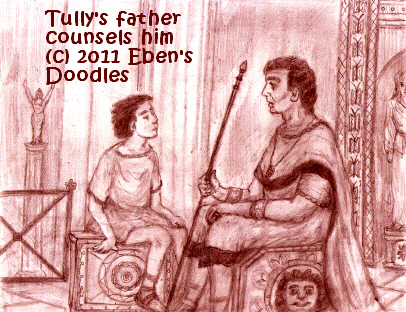

"Son, it is time to inform you of some things, important things.

As you know, there have been some things going on in this house that

seem most strange to me, to you no doubt, and to the servants as well.

They cannot be explained. It is not true the gods are against us, for

if there are no gods how--"

Tully's mother cried out, "How can you speak so to your son,

husband? That is impious talk!"

His father shot his mother a glance, then firmed his jaw, and continued.

"Anyway, the gods of Olympus and Roma have grown old and enjoy such great power over men anymore. Everyone knows that, and

I am just telling you what most people I know believe about them.

"But what about the Jews' god, is he dead too like Jupiter and Mercurious, Juno and Minerva and Venus

and all the rest?" shot back Tully.

His mother gasped and put a hand to her cheek.

His father too looked shocked, and seemed speechless for a few moments.

"Well, son, no, he may not be dead, if what I have heard from my friend

is true, I think, that he is a jealous god and is punishing his Jews for abandoning himn for other gods."

Tully was emboldened to continue. "I have heard from Aaron of a Christian god and son of god too named Christus, and a servant

too

told me about him, that he is Savior of the World and born of a virgin and rose from the dead after

the emperor killed him on a stake--is

he dead like all our ancestors' gods? Didn't he rise from the dead like our cook Maconius said?"

His father shook his head as if Tully were speaking nonsense. "Give no ear to servants' foolish talk. I never

intended to speak about religion with you like this. But now that you

want to know, and you are almost a man, it might as well be now. As for

your question, I can't answer to it, as my friend told me nothing

about any Christian God, just that where was for a time the one called Christus, whom he

does not believe in and calls an imposter. So he can't be a god. And he couldn't

have risen from the dead. Anyway,

the Jews believe only in the invisible One True God,

called by a name they dare not utter, they reverence it so much."

"Can I go play with Aaron today, father?"

"Oh, so you tire of these questions of religion and gods so easily," his father laughed.

Well, you're just a boy, not yet a man, it is plain. Yes, you may!

It would be good for you to get out of this house--

and when you return maybe it will be set more in order.

You may even go with me to select a new watchdog, if you

like, and take your friend too."

Tully rose. "Is that all, father? May I go now.

I want something to eat, and then I will

see my teacher and do my studies."

"No, Tully. I just remembered. Aaron is not at home.

Nathan and the whole bar-Shlomo family has gone to Stabia, and won't be back for

maybe some days until the his father's affairs are settled. Didn't you hear my friend tell me that?

I thought you would be listening in."

"I did hear something, father, but I forgot when it

might be. I wanted

to see Aaron so today!"

"Yes, he is a good companion for you. He's not like the others scamps

of our insula--I

hardly know what they will lead you into doing. I caught

several hanging around the door of the gambling house the other day and

sent them home! But you will have

to wait for Aaron's return. But you may go out with me

later today, after your breakfast and time with

your teacher."

Tully's face brightened. "I'd like that, father!

Will he be the same kind as Sulla? Sulla

was a mean dog, and wouldn't let me pet him.

He growled a lot too. Can't we get a dog I

can take with me on a leash and let sleep with me?"

"No, son, I know you miss having brothers and sisters for playmates, but dogs aren't for such things. Whatever we get, has to be fierce

as possible, or robbers won't fear to come and

break in. You understand that, don't you?

A good dog will be able to keep them out. If you

want a dog, it has to be another kind,

not a watchdog."

"Could I have a dog of my own then? I so want

a big, black mastiff with a white crown and white

patches

on his legs, like the one a friend of mine has!"

Tully heard a noise and looked up. His mother

was signing to his father and shaking her head.

"Well, not now, Tully. First, we must get

the household back in order. Now go and get

something to eat and prepare for your teacher.

As for the other matters I intended to

speak about with you, they will have to wait."

Tully was glad to hear that last

remark, for he wasn't keen to hear about

those "other matters"--they sounded too

serious to him, and might entail the family's

moving from Pompeii, the worst thing he could

think of.

He scampered off to the kitchens, and

Maconius was there preparing the

noon meal, and had fresh baked

rolls and other things to

give to Tully along with milk

and some honey for a treat.

For Tully at least, the rest of the morning passed quite routinely. His teacher, a

Greek, came and taught him Rhetoric and made him give a little speech to

sharpen his delivery and handling of speaking points. His other

studies in math and music proceeded as usual too. He had got through

them and his teacher had departed for the day, and

was wondering if he had to do his studies now or later, when his

father interrupted him. It was now forenoon, and time for another

meal.

But there came no servant to call him. Instead his father

appeared and sat across from him at the table in the study. His face looked most solemn,

and Tully let his writing tablet slide from his hands and forgot

the things he was finishing on it in his Greek essay on

the Persian wars and the sack of Athens by the Persian king.

"I must speak to you privately, son. Lunch will wait. That is best, for I don't want to upset your

mother, and she doesn't want to dine anyway, and is keeping to her room. Now be a man, a

true Samnite, and

listen carefully."

That got his attention. He straightened up, and waited.

"Cornelius Sulla was leader who ruled with the consent of the Senate, and he was without mercy, but

the gods spared us from his destroying hand after he defeated our brave Samnite defenders, which

were betrayed by false counsel and fought in the midst of the foolish circumstances against him, and lost.

Even Sulla could not bring himself to destroy such as splendid city as this, so

he relented, and took away our freedom, but allowed us two governors, making us a colonia,

without autonomy and self-government as some cities under Rome enjoy. But evenso,

our city was spared destruction, and soon Sulla's own family moved here to enjoy

the beauty of the city. The finest house in this city is one of those they built here.

"Those days are past, however, and we entered into a prosperous period under the

Romans, despite their high taxes and our inferior status as a colonia. Then came the violent shaking of the earth that leveled most of our city.

Yet our industrious Samnites rose up to the misfortune. They did not flee but stayed and

rebuilt the city better than it was before. We also stayed, when we could have removed to Roma, where we already had some

business. Pompeii is our native city. That is how

we Septimii feel! Pompeii flows in our veins like our blood! Pompeii is our

heart beating in our chest. Our pride and lineage are Pompeiian. We will always be proud

sons of hers! Long live our city!"

Tully had heard these lofty, somewhat pompous sentiments concerning the city and his Samnite family lineage before, so they were not surprising or

even all that interesting to him, but he kept a respectful

expression and tried to keep attentive and not let his eyes wander.

"My civil case has gone forward very well at the imperial court, I have

just been informed by courier. We are due compensation for all our family's losses

under General Cornelius Sulla. It will be considerable too! We will be

very wealthy again. I have been a garum merchant a long time now, but I may turn this business over to

a manager here, and we will move the household to Roma, where I will take

a palace on the Palatine that befits our ancestors. We can move in imperial court circles, as

we will be sought after, once the decision is made public and our

family fortunes fully restored. Do you understand me, son? I want you to

know this, in case something ever happened to me, and you need make

claim to it. You are our only son--and much depends on you once your mother and I

pass to the underworld."

He felt close to tears, but manfully held them back.

"Son, I will do as I feel is best with this household. When the time comes, I will decide, and

you will hear of it. So that is all I wish to say about it for now."

Tully's face showed his unhappiness. But he couldn't challenge his own father. "Is that all, Pater? May I go and play now? I've finished all my

studies in advance for tomorrow."

His father sighed. "Yes, I suppose you can! It is nearly noon, and

I must try to get your mother to eat a bite or two, or she will waste away if I let her!

She has lost flesh lately, with all her worrying and stewing about

inconsequentals. Women! Always so temperamental! They love to stew and fret about all sorts of that

amount only to trifles in the end! But not even heaven and the gods

can change them! Even Minerva and the other goddesses of old acted this way--

and high heaven was always in a stir because of it!"

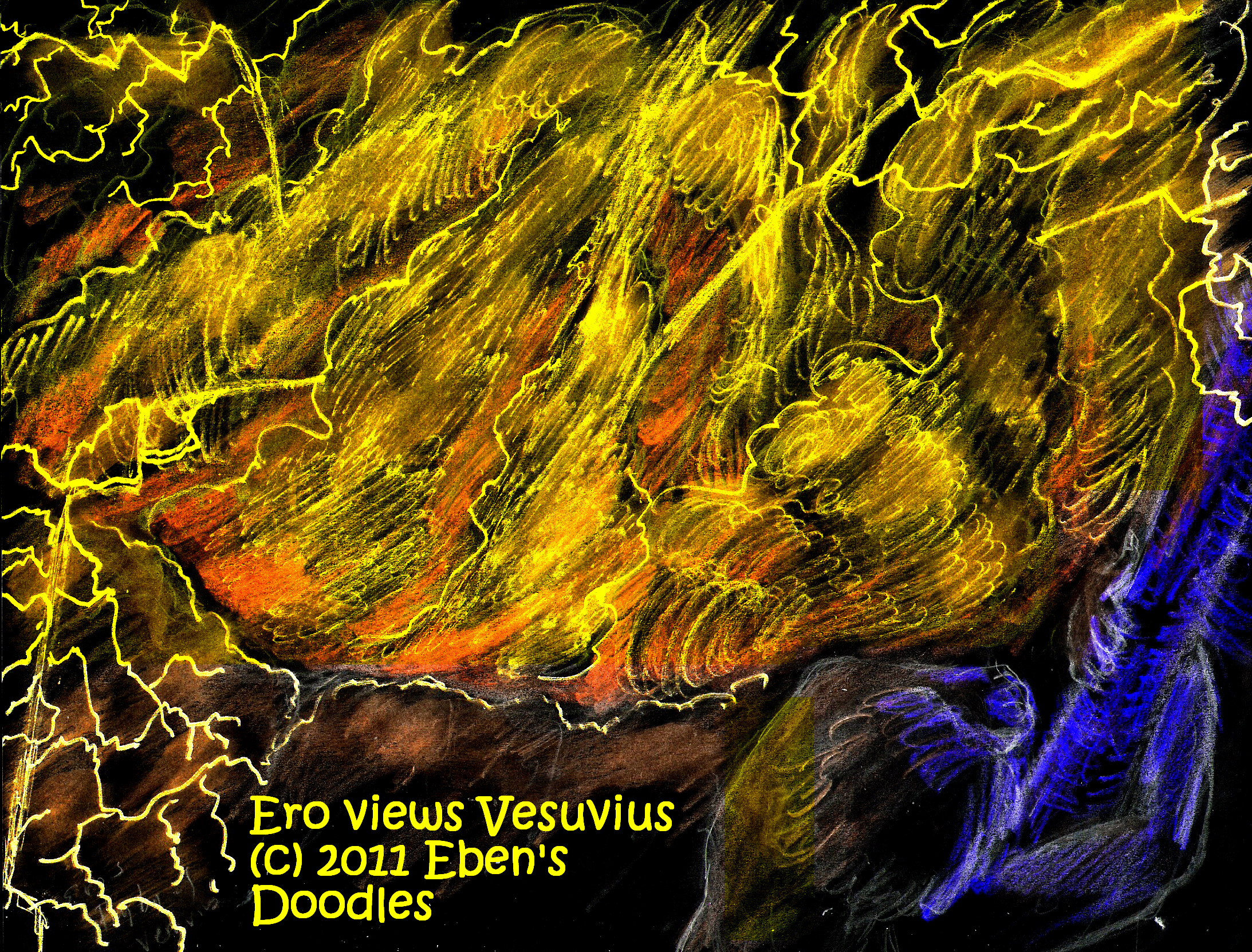

Tully rose from his seat, and was about to take a step when they heard clattering, rolling objects on the roof overhead. Some of the things fell through the compluvium and landed in the

water of the pool too, hissing as they struck the water.

"By Jovius, what hit the roof?" his father cried. "It landed too hard, it can't be rain. Some

ruffian in the street throwing rocks at my house? If I catch the soundrel, I'll thrash him!" He sprang up to go see, Tully

right behind him. But before going out to the street, he paused and with his hand fished out a dark object from the impluvium,

then jerked his hand away from it, letting it fall to the floor.

Tully touched it, and it burned his finger, which he yanked back.

"What is it, Pater?"

Cassius's voice was full of wonder. "I don't know, son.

Something hard fell out of the sky, and it is very hot, and dark

like the black rock on the mountain. Could it be from the

same place? Or did it fall from heaven itself and is

a sacred thing like the sky-stone Jupiter has in his crown in Roma?"

His father moved quickly to go and went out the door take a look at the mountain.

In the street, he found whole families, all hurrying as fast as they could,

making for the closest gate of the city, or if not there first, to gather up

other family members and possessions.

A nearby brothel was turned out at that moment into the street,

its clients and their prostitutes evidently frightened by

what was happening.

Since the hard, burning objects were still pelting down like bombs on the city

from darkened clouds over the mountain,

the women screamed and hurried off, without waiting for carriages. The

house owner was arguing with the operator of the

bawdy house, and Cassius heard the owner was demanding

some compensation if they all abandoned their lease suddenly

like that.

The bawdy house proprieter pushed the house owner back violently,

and he fell down, then rose partway, shouting for officers

to come and arrest the man.

Swearing at him, his attacker hurried off to catch up with

his women, while some of his clients pursued him, demanding their

money back for yet certain unprovided services.

But this distasteful scene was not

so worrisome to Cassius as others. As he looked up at the churning dark clouds, he

saw lightnings and and flashes of what looked like huge flames of

fire jutting upwards into the high heavens.

A dark, wet, heavy, pellet-like

material then began falling in huge swathes and clumps upon the whole city, darkening

the sky further. Roofs began to fail all over the city, unable to bear

the load of it.

A horrible presentiment seized Cassius. Was this the end of the world for them?

The temples--what good were they now? The gods had abandoned

Pompeii, it was clear from what he was seeing. Pompeii was rapidly

falling apart before his eyes. Wasn't this the judgment of the

Jewish god Jehovah, who was angry at them for what Vespasianus

and Titus had done to his temple in Jerusalem?

He fled from the street back indoors his own house,

slamming the doors, but he did not bolt them. Why bolt the doors now?

His house was no longer a safe refuge, it had become a death trap, a tomb!

He thought immediately

they must all go, taking whatever they could, but

leaving as soon as possible for their own safety's sake.

But then his heart nearly stopped with cold terror at what

he had done: he had sent all the horses away. Their carriage and

wagons were useless! They would have to flee on foot! But could he induce

his wife to do that--run in the streets? She had never run

anywhere, even as a girl. Ever since Tully's birth, her health had

not been good, and her movements had been severely restricted. She

hardly ever went outdoors, and then only in a carriage.

He passed by his son who was still fishing out

hot rocks from the pool with a piece of pottery, and

went directly to his wife's side.

"Drusilla, we must leave! Something has gone

very wrong with the mountain--it is

spewing up fire and clouds, and there is

lightning flashing all round it. It is looking very dangerous."

His wife stared at him for a moment, her eyes

rigid, and he saw his own terror reflected in

her expression.

"No!" she screamed. "I am not leaving!"

"But you must! Everyone is going! Everyone!

The streets are full of people leaving the

city."

"But how will we go? You sent away our horses!"

"I will go hire a horse to hitch to our carriage,

or if not that, hire a carter and wagon and he'll

drive us out. You can take some nice things with you, if

you will only hurry."

There was a huge crash on one side of the house across the

impluvium. Tully ran in a moment later.

"Pater! Mater! A big smoking rock fell right through the roof!"

Hearing this, Tully's mother groaned, and turned her face

away, sobbing.

Cassius tugged at her arm. "We must go now!

Leave all the things--there is no time, we can take nothing. We must

get up and go as we are, for

our lives are more precious than these things.

We can always replace them. Maybe in the street

we can ride with someone else in his carriage or wagon."

"I'm not going!" his wife sobbed into her

bedclothes. "Go without me!"

Cassius was beside himself. "I--I cannot leave you."

"You know I can't run in the streets like a commoner--I could never do that! And my legs are too short, I can only move slowly. No,

I won't leave my home, no matter what the mountain does to me. You go, let me die here,

where I am, in my own home!"

Cassius put his face in his hands, then he

rose and took a few steps away toward the

door, paused, and turned around with a grim face.

"Tully, I have to stay with your mother.

We will be all right here, the roof is new and good, with strong

supporting timbers. But you must go. Run as fast

as you can, and go to the ranch and