"A-Yang-E-Lokh-Tokh,"

"God's Man,"

Carrying the Gospel to "Alayaska," the "Great Country," by Mrs. C. K. Malmin

--Prepared for the 50th Anniversary of Mission Work in Alaska--

Five dogs were hitched to the tow line, and they pulled five miles along the beach to the channel, a narrow strip of choppy water, the entrance to Grantley Harbor. Here the dogs were tied and we rowed across to Teller.

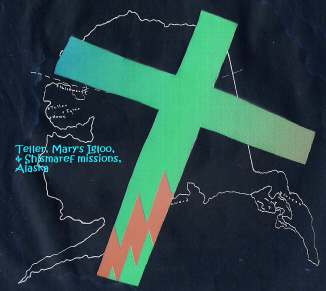

The "Kotzebue," a stern-wheeler, was moored at the dock. Alongside lay the loaded barge. We waved goodbye to the native boys who were pushing off again in the dory and sent a last greeting back to the Mission. We were leaving on the last lap of our long journey.

The trip inland to Mary's Igloo was an uforgettable experience. We left Grantley Harbor and entered the Tuxuk, a winding, deep fjord that linked Great Salt Lake with the sea. It was thirty miles to the mouth of the Ageopak river. We followed this winding water course to Davidson's Landing, and on through Kotzebue Slough, and into the Kuzitrin River.

To our right, as we traveled eastward, loomed the rugged Sawtooth Range that was to become such a well loved part of the Alaskan scenery.

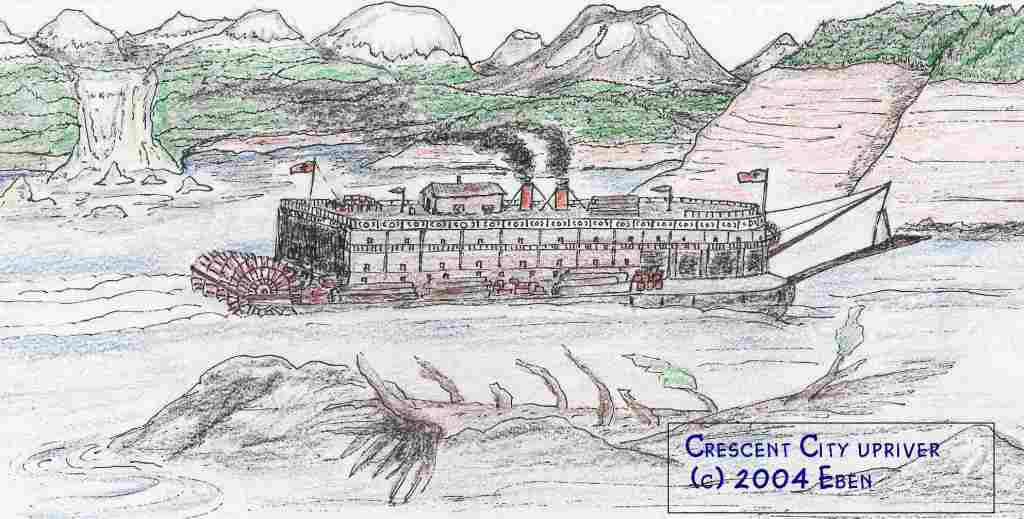

At last, late in the afternoon, we came to Mary's Mountain. A little way up the hillside we saw a cluster of white crosses. And then a bend in the river, hid them from our view. Beyond lay the village. We reached home.

There was Oquillok and his young son Opollok, who had come from Pt. Hope to learn from Pastor Brevig more about the Christ that a Christian had told him about.

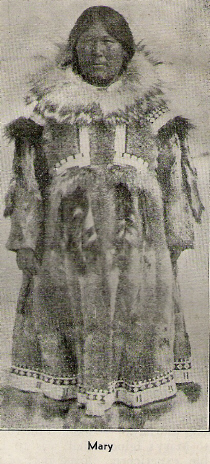

And of course you must hear about his wife Mary. It was in her Igloo that the miners found shelter on their way to the mining country farther north. It was such a pleasure to talk to her. She would always bring her Bible. Before she left she would ask a little shyly, "Will you please read something?"

Then came the year 1918. In April we heard that the Mission at Teller had burned. Practically everything was lost. The missionaries and the four native children had to find shelter in the old government buildings. Friends at Teller made it possible to set up temporary house-keeping. The mission was rebuilt that summer, but they had no more than settled for the winter, when the flu epidemic came.

The whole village was stricken. Rev. Fosso and Miss Enestvedt were desperately ill. Only Mrs. Fosso and little three-months-old Paul escaped. She nursed the sick, laid away the dead, and fed those who could eat. She risked attack from half-starved malamutes to get ice for water. She tried to visit the natives who were ill, and bring help to them.

As many as she could find room for, she brought into the mission. Many died there. But her courage never failed for she had learned to rely on her heavenly Father for strength.

She carried on, from day to day--forgetting herself in her struggle against terrific odds, until one day she realized that her baby was fretting because he was so hungry. She had been too busy to eat. At last the sick ones recovered. There were six native adults left, and 34 children. Over a hundred were dead.

The missionaries slowly regained their strength as the long dreary winter dragged on. The following summer Miss Enestvedt was glad to be relieved, for she was completely spent. The Fossos stayed on to complete their three year term and then left, in the summer of 1920, with Leonard Suluguak, who was to study at Red Wing Seminary, to prepare himself to become a native evangelist.

At Mary's Igloo forty of our natives died. We were daily exposed to the contagion, but we were spared. Instead a little daughter arrived to gladden our home. She was baptized and was named Solveig Corinne. The natives called her "Kaumarikh,"--Sunshine.

I would like to tell you of the simple, child-like faith that was so evident in the Eskimos. They believed that prayers would be heard and answered.

Topcokh and his wife were the only flu survivors at No. 1 Reindeer Camp. They were ill and thought it only a matter of time until they too would die. But first they must see the Missionary.

Twenty miles asway was Igloo and the going was rough. Yet they stumbled along, falling from weakness, sometimes fainting away. But always one would pray for the other and after a long bitter trek they stumbled into the village. Just the day before, the missionary had been told that all was well at No. 1 herd.

Topcokh and his wife asked to be given the Lord's supper, and then they lay down to die. But the Lord willed otherwise. They lived to praise Him for His Providence and mercy. Many an incident could be told of the spiritual growth of these simple primitive people. Their eagerness to hear God's word brought joy to the hearts of the missionaries.